The Power of Initiative

The lessons India can learn from cities that were able to transform transportation and mobility.

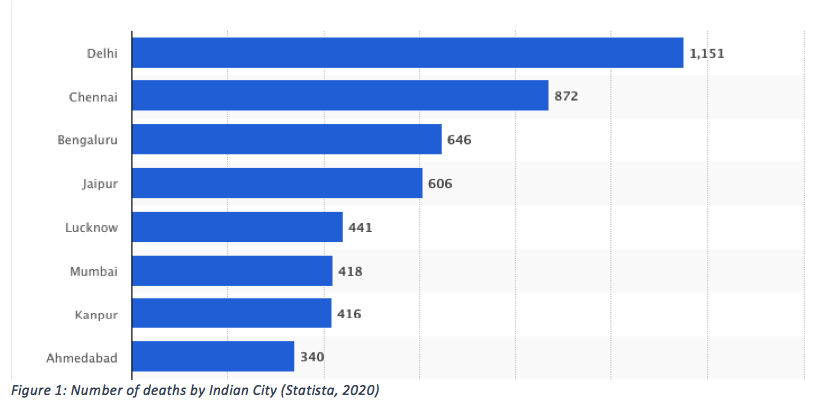

To say that Indian cities have largely neglected sustainable transport would be an understatement. Urban cities have largely been designed to cater to vehicles; designed to ensure that these vehicles can get from place A to place B as rapidly and comfortably as possible. In doing so, the needs of vulnerable road users are neglected. According to the Indian Government, one citizen is killed due to a traffic accident every three and a half minutes. Yet, most continue to move forward believing this is acceptable and unavoidable – that this is ‘just the way it is’.

Figure 1: Number of deaths by Indian City (Statista, 2020)

When looking from an Indian context at cities that have better transport policies, safer roads and cleaner air, achieving what they have seems impossible. Cities like Amsterdam, Copenhagen and even Bogota have systems and infrastructure in place to ensure that sustainable transport remains at the forefront of development. However, these cities didn’t just happen to be designed this way. All 3 cities at one point had a transport system that catered to vehicles. It took initiative, strong-willed individuals, citizen involvement and more to achieve this transformation, and it took over several decades. Let’s delve a little deeper into how they were able to do so.

What did Amsterdam, Copenhagen and Bogota do right?

Amsterdam

Ask anyone who has ever tried to make their way through the centre of Amsterdam and they’ll likely all say the same thing: the city is built for cyclists and pedestrians, not vehicles. It’s easy to think that this is ‘just the way it is’ in the Dutch Capital and that the abundance of cycle paths and public space for pedestrians has existed since the beginning of time. This is far from the truth. During the 1950’s and 1960’s, when the Dutch economy had started to boom in the post war era, more and more individuals were able to afford cars and urban policymakers even saw it as the transport mode of the future. There were entire neighbourhoods which had their physical urban fabric destroyed to make way for motorised traffic.

The number of casualties on Amsterdam’s roads rose to a peak of 3,300 in 1971, with over 400 children falling victim to these as well. To give a reference point, 1,180 lives were lost on Delhi’s roads in 2021, about a third of that of Amsterdam. This loss of lives led to several movements by different action groups, the most memorable of which being the ‘Stop De Kindermoord’ which translates to ‘stop the child murder’. Its first president was the former Dutch MEP, Maartje Van Putten, who was witnessing and was horrified at this major loss of life, and the number of children that were victim too. Among other things, she was a mother that wanted to ensure that her children were safe on their streets.

Other action groups started to form around this time too including the Dutch Cyclists’ Union 2 years after. In 1973, the Netherlands faced an energy crisis, leading the government to proclaim a series of car-free Sundays to remind people of what streets used to be before the hegemony of the car. Whilst the energy crisis was possibly the trigger for the government to begin prioritising sustainable transport, the benefits of the shift were easy to see. Cleaner air, livelier spaces, happier citizens and fewer deaths. Gradually, as Dutch politicians began to recognise these benefits, they shifted their transport policy to promote and accommodate pedestrians and cyclists as a priority over motor vehicles. The Netherlands now boasts 22,000 miles of cycle paths. The Dutch Cyclists’ Union has over 34,000 members and traffic fatality numbers are far lower, with 582 deaths in 2021, nearly 6 times lower than that of 1970 with a population that has 200,000 more people.

Copenhagen

The city of Copenhagen has been working toward improving their non-motorised transport infrastructure for over 100 years. However, it was the same energy crisis in 1973, that led to major petroleum shortages, that acted as a trigger for greater change. There were a few common themes for both Amsterdam and the Danish capital:

- Car-free days were implemented by the government to promote non-motorised transport by allowing people to experientially reimagine what their streets could be.

- Citizens clearly demanded greater space and better design for non-motorised transport. The late 20th century saw a host of movements by citizens and the formation of the Danish Cyclist Federation in Copenhagen that constantly challenged the state of the infrastructure at the time. This demand forced city planners and local governments to focus on better non-motorised transport design.

- Most importantly, both cities took several decades to see positive change. This required both a high level of patience and investment. Around the 1960’s, Copenhagen began to remove the amount of parking space available to cars by 2-3% a year, which made alternative transport options more attractive, and freed up space for walking and cycling lanes. Since then, there has been an over 600% increase in pedestrian-friendly space in Copenhagen. Rome wasn’t built in a day and that applies to all urban cities in the past and today. According to Forbes’ position on cycling and its socio-economic impact on Copenhagen, the city now saves up to $34 million every year in avoided air pollution, accidents, congestion and wear and tear on infrastructure. Gradual change may be the only way, but it reaps rewards.

Bogota

The transformation in Bogota came through a different route. In the mid-1900’s, Bogota was considered as one of the most violent cities on the planet. This violence peaked in the 1990’s, largely due to drug cartels in the country. It was former mayor Enrique Penalosa, that recognised the importance of building back Columbian cities with an equitable outlook; cities that put people and their safety first.

Penalosa’s first stint as the mayor of Bogota was from 1998-2001. During this term, he was instrumental in the transformation of Bogota from one of the world’s most violent cities by focussing on the expansion of public services and institutions, most notably the TransMilenio BRT system, now seen as one of the most successful public transport modes worldwide.

Penalosa was a major advocate of leveraging social institutions to create a greater level of equality and democracy for the citizens of Columbia. His most impactful legacy in this regard was the rejuvenation of sidewalks and bicycle lanes, viewing both as basic human rights. Pedestrianizing a street, he believed, was the most important element of what an inclusive and equitable city should look like. Fast forward about 20 years from Penalosa’s first stint, Bogota is now home to a city-wide cycling network that covers more than 600 km of street space – making it the largest in the world!

Once again, the change was gradual. Columbia’s journey to become a cycling haven began around the 1970’s, with the introduction of Ciclovia. The brainchild of architects Jaime Ortiz Mariño and Fernando Caro Restrepo, the idea behind the event was that select major streets in the city would be blocked off to cars between 7am and 2pm on Sundays and national holidays, giving runners, cyclists and pedestrians space to exercise and enjoy in a safe space. Similarly to Amsterdam and Copenhagen, this gave citizens a chance to reimagine their streets, and in turn, demand safer streets. What started in December 1974 as an unofficial event has become a weekly staple of life in Bogota, inspiring other car-free initiatives across the world. Ciclovia individually was not the solution to the problem, as it only closed off the streets to cars for 7 hours a week, the other 161 remaining the same. However, it instilled a demand for public streets that catered to people.

So what can India learn?

Major metropolitan cities in India have largely neglected the importance of safe, inclusive and accessible transport infrastructure. Around 30-40% of road users are using some form of non-motorised transport, but our street design is largely centred around providing ease to vehicle users. Looking at the traffic death numbers in our cities, it’s safe to say this is a crisis. However, seeing that other cities have been able to escape such transport crises, it’s important to recognise that we can too.

What may be most important to understand is that change will be gradual. It can, and often will, take decades to make change. There is no silver bullet, or sure-shot solution to the transport problem, but looking at best practices such as those above, as well as what has worked in this country in the past, we can begin to put systems in place. For example, car-free days have been an important element of change for many countries. In India, we have movements such as Raahgiri Day which operate along the same theme – to provide a safe, vibrant public space to show the citizenry that our streets do not belong only to vehicles.

India is still a developing nation. As our cities become urbanised, they become more motorised. It is essential therefore, that we foster a demand for better transport infrastructure in our cities. We need to learn from cities like Amsterdam and Copenhagen – to learn that until we as a citizenry do not actively demand our right to safer roads, it will be difficult to see progress. A good example of the effectiveness of this demand in Gurugram is the implementation of Gurugram Vision Zero to reduce road traffic deaths. Social organisations, NGO’s, the citizenry and more have been demanding that our roads be designed to be made safer for vulnerable road users. It took several years to get it started and will take several years for change, but it represents footsteps in the right direction. Indian cities are not doomed to unsafe roads but it’s difficult to see change unless we raise our voices to the problem.

Creating a high-quality public transportation system is the backbone of any city. This can be seen as an absolute fact. The BRT system in Bogota, namely the TransMilenio, took years to be successful but is now seen as the pinnacle of bus transport. The Delhi BRT failed for many reasons, but mostly because it was poorly implemented. No proper corridor provided, poor PR for the project and lack of initiative in general meant that it was always going to be hard to succeed. Investment and patience into such a project would have almost certainly led to better outcomes in the long-term, as what happened with the Indore BRT.

There is a need to understand our current context, identify the issues, and make changes that will reap rewards in the future. Current public space needs to be allocated more efficiently; streets must be designed with vulnerable road user safety in mind, and safe and accessible public transport must be at the forefront of transport policy. The value of investment into such transport infrastructure when looking at safety, at the economy and general happiness of the citizenry is clear – now India just needs follow suit.

ALL CONTACTS

- C-157, Anand Vihar, Vikas Marg Extension, Delhi, India, 11009

- Office +91-8826865797

- raahgirifoundation@gmail.com

- Copyright All Rights Reserved : Raahgiri Foundation

- raahgirifoundation@gmail.com